The Nobel Prize in Literature is awarded to writers for the breadth and depth of their lifetime achievements rather than for a single book, unlike the Pulitzer or Booker prizes. When the Swedish Academy announced the award for the Korean author Han Kang last year, it specifically cited her novels for its lyrical intensity and its fearless engagement with historical trauma. The committee praised the works for exposing both the fragility and resilience of human life through prose that is at once poetic and unsparing.

In her Nobel Prize lecture, Han Kang posed two haunting questions: “Can the past aid the present? Can the dead rescue the living?” These questions, she explained, had long guided her writing, as she sought to understand how the memories of atrocity victims might illuminate and sustain the lives of those who remain.

Han Kang’s latest book We Do Not Part, published in English in 2025, begins in the stillness of falling snow, a whiteness that both conceals and reveals. The snow is not purity but memory itself: soft, silent, and heavy with what cannot be buried. From its opening page, the novel transforms landscape into testimony. Every flake seems to whisper names erased from the official record, and every sentence glides across the fragile line between remembering and forgetting.

At the center of the story stand three women: Jeongsim, a survivor of the Jeju 4·3 Massacre; her daughter Inseon, who carries that unspoken inheritance; and Kyungha, the narrator, whose friendship with In-seon draws her into the orbit of the past. When Kyungha travels to Jeju to care for Inseon’s parrot and finds it dead, the event feels at once accidental and symbolic, a small death that opens the door to all the others the island holds. Through these women, Han traces the invisible network of grief linking generations who live with history’s unhealed wound.

When the narrative reaches Han Kang’s account of the Jeju atrocities that occurred nearly eighty years ago, the novel shifts into a somber, harrowing register. Her depiction is unflinching yet never sensational. She writes with a calmness that makes the horror more unbearable, letting images emerge with the clarity of remembered nightmares: bodies buried beneath volcanic soil, children hiding in caves, the smell of burnt grass lingering long after the flames. The violence is not described to shock but to testify, to insist that such pain, once lived, cannot be erased by silence or time.

Her language remains spare, the sentences measured and cold, as if grief itself has stripped syntax of excess. What makes these passages so harrowing is their restraint; Han Kang refuses to turn history into spectacle. Instead, she gives the reader the slow, unbearable task of witnessing—the ache of imagining each death individually, as someone once loved. Through this austere precision, she transforms the massacre from a distant historical event into an intimate moral reckoning, confronting us with the cost of forgetting.

To “not part” in Han Kang’s vision is not sentiment but discipline. Forgetting implies a clean break, a return to normal life. But her characters’ refusal to part becomes a form of quiet defiance, an insistence that the dead remain among the living, not as ghosts but as responsibilities. The novel turns remembrance into an ethical act, suggesting that to live humanly is to keep faith with the lost, to hold space for what cannot return.

The prose itself performs this ethics. Han Kang transforms ordinary images into vessels of emotion and thought. Her prose moves slowly, as though language itself were tracing the edges of silence. Snow, birds, and trees recur not as decorative motifs but as analogical mirrors of the characters’ inner states: the snow evokes the stillness of grief and the fragility of memory; the bird, the flicker of life that refuses extinction; and the tree, the quiet persistence of those who remain rooted despite loss.

Her analogies unfold organically, never explained but felt, allowing the natural world to carry moral weight. She often juxtaposes warmth and cold, light and shadow, to express the paradox of survival after tragedy. The result is a prose that feels both transparent and haunted, each sentence pared to its essence, yet resonant with what it cannot quite say. Through this spare lyricism, she transforms trauma into image, memory into rhythm, and mourning into an act of aesthetic grace.

Unlike her earlier novels Human Acts, where collective trauma and public grief take center stage, We Do Not Part turns inward. It asks what happens after the shouting stops and how people continue when there is no audience left to witness. Han Kang’s gaze falls on the private labor of remembrance: the tending of small fires, the daily work of not forgetting. She shows that memory is not an archive but a living pulse, a rhythm one must keep.

By the novel’s end, the snow has not melted, and the dead bird does not rise again, at least not in the world of fact. Yet in Kyungha’s mind, it continues to lift its wings. That imagined motion becomes the book’s final gesture: the persistence of life within loss. Han Kang suggests that we cannot choose what to remember, only how we will carry it. To carry is to love, and to love is to refuse oblivion.

Thus, We Do Not Part is, as the title suggests, not a novel of departure but of endurance. It asks the reader to inhabit the same patience as its characters, to breathe slowly, to look steadily at what history would rather hide. In doing so, Han Kang redefines mourning not as darkness but as a fragile form of light: the light of those who remember when remembering is no longer required.

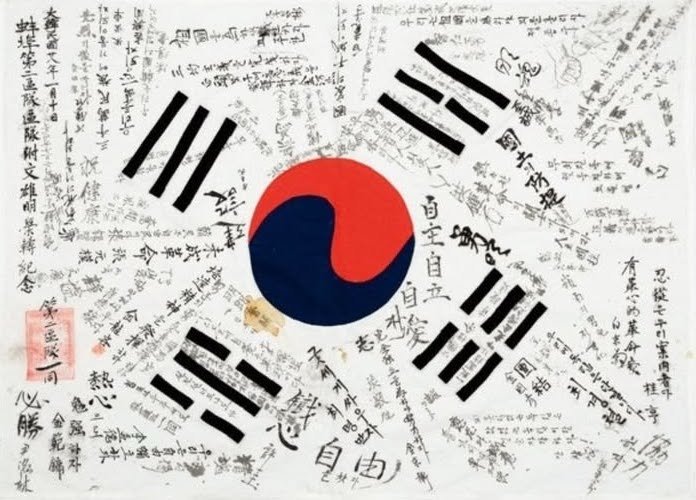

To answer the questions Han Kang posed in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, we might look to a moment from Korea’s recent history. When the former president Yoon Suk-yeol declared an illegal state of martial law and dispatched storm troopers to the National Assembly to arrest opposition lawmakers last December, ordinary citizens surged forward to defend their democracy. They stood unarmed before soldiers, risking their lives to protect the Assembly and the constitutional order. Their defiance, followed by the Assembly’s impeachment of Yoon and the Constitutional Court’s ratification of that decision, became a living response to Han Kang’s haunting inquiry.

These citizens acted with the memory of past tragedies engraved in their minds, knowing too well what tragedies had followed every declaration of martial law in Korean history. In that sense, the victims of the 1948 Jeju Massacre and the 1980 Gwangju Uprising have, in a profound way, rescued the living; their suffering became the moral memory that guided the nation’s courage.