On April 4th, Yoon Suk-yeol, the former president who bewildered and angered Korean citizens on the night of December 3rd by declaring illegal martial law and sending storm troopers to the National Assembly (Korea’s version of Congress) to arrest Democratic Party lawmakers, was finally impeached and removed from office.

This victory belongs to the ordinary people, who marched through the streets for nearly four months demanding justice. Young voices, especially those of women, led the way, their courage fueling every step of this historic moment.

I joined numerous protests calling for Yoon’s impeachment, sitting among over a million resolute faces outside the National Assembly. As I looked around, I felt an immense surge of hope; in their hands, Korea’s democracy felt vibrant and secure. Though the cold bit at my cheeks, their bravery kindled a warmth no winter could extinguish. All the while, BTS’s Fire blazed through the freezing day, a perfect anthem for a people who had reignited the flames of justice!

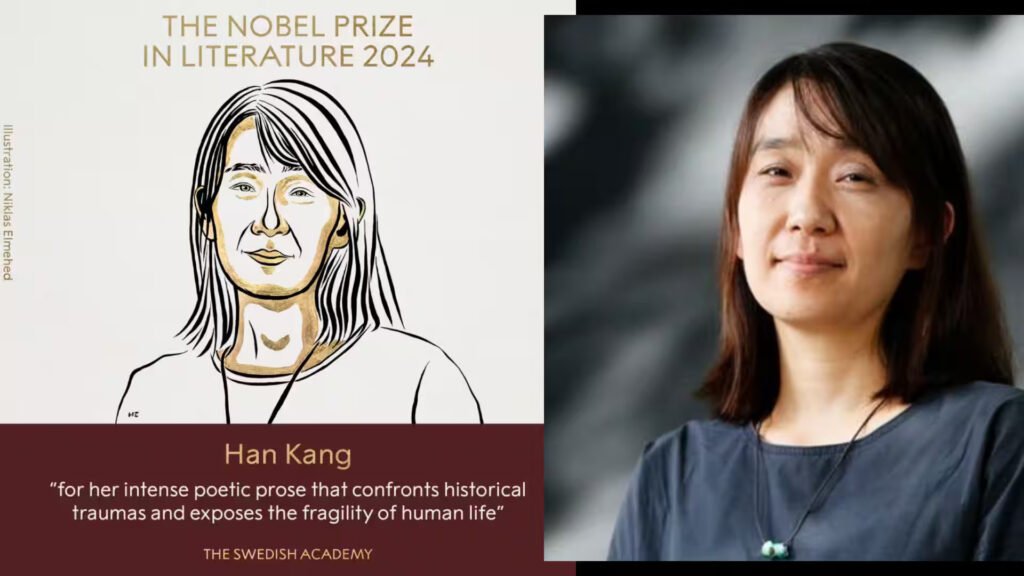

In her acceptance speech for last year’s Nobel Prize in Literature, Korean writer Han Kang asked, “Can the past aid the present? Can the dead rescue the living?” Her stories deal with the trauma of massacres committed by military dictatorship governments following the declaration of martial law in Jeju in 1948 (yes, the island featured in the recent Netflix drama series “When Life Gives You Tangerines) and in Gwangju in 1980.

While writing her books, she had pondered how the past might help the present, and how the victims of massacres could guide those still living. The impassioned rush of ordinary citizens, who risked their lives to shield the National Assembly from stormtroopers, and the Assembly’s subsequent impeachment, later ratified by the Constitutional Court, together provide a powerful answer to her questions.

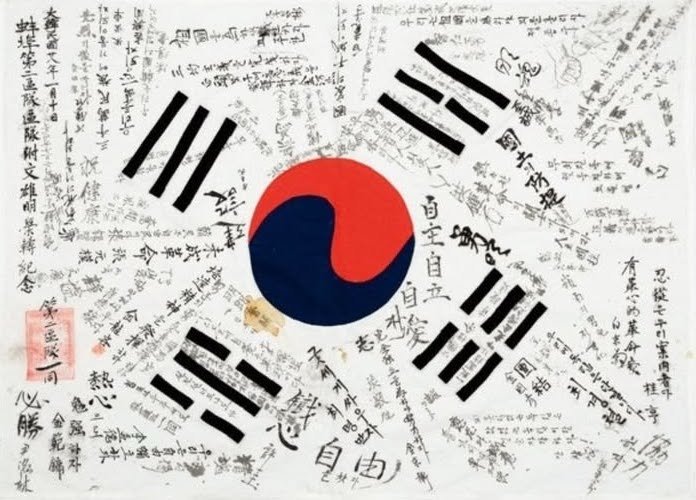

I want to share with you some remarkable, untold stories of Korean citizens’ courage, a courage born from those who have lived through or read about the past atrocities committed under martial law. These moments, drawn from eyewitness accounts and largely absent from mainstream media, are simply amazing.

Among the thousands who rushed to the National Assembly to defend the progressive Democratic Party lawmakers, some showed up in slippers, having run straight from their homes.

Women in their 70s (photo below) shouted to one another as they formed a line in front of the soldiers, declaring, “Let us be the first to be shot. We’ve lived our lives, let’s do this for the young people.”

The National Assembly’s female staff in their 40s and 50s confronted soldiers who smashed windows to break in, slapping them and pleading, “I have sons your age serving in the military! Stop this!”

Middle-aged men lay their bodies in front of armored vehicles marching toward the Assembly, yelling, “You’ll have to go over our cold, dead bodies.”

Lawmakers’ aides, staff, and journalists rushed to the entrance from inside the Assembly, forming a human barricade and daring the soldiers to fire.

With rogue police officers blocking the outer gates, Democratic Party lawmakers secretly climbed over the Assembly walls. Seo Mi-hwa, who is visually impaired, scaled them alongside Lee Jae-myung, the party chair and likely Korea’s next president.

Citizens of all ages encircled the Assembly’s wall through a bitterly cold night, standing guard long after martial law was lifted, fearing the soldiers might return.

High school and college students, mostly young women, sat along the walls the next day, working on homework and preparing for final exams. Two high school girls even traveled from Ulsan, over 300 kilometers away, just to stand watch.

A group of high school students handed out cookies wrapped in packaging that read, “I couldn’t vote in the presidential election, but I will make the impeachment happen.”

In the restrooms of subway stations near the Assembly, people left everything from tampons, hot packs, food, masks, water, and bandages to chocolates for protesters on their way.

After dropping off a protester at the Assembly, a taxi driver canceled the credit card payment.

Perhaps the greatest heroes were the hundreds of young soldiers sent to arrest lawmakers. Confused and unprepared for the sea of civilians, they held their ground without escalating. Though shouted at, pushed, and provoked, not one struck or shot a protester. Aware of what happened in Jeju and Gwangju, they indeed proved that the past aided the present, and that the dead have rescued the living.

You may have seen the photo or video of a courageous young woman—once a news anchor, now a Democratic Party member—grabbing a soldier’s gun. What you might not know is that Korean soldiers are trained to shoot to kill anyone trying to seize their weapon. Yet the soldier, barrel pointed at her, kept his hand on the gun and carefully avoided the trigger, opening his palm slightly to prevent an accidental shot.

A few soldiers who broke the windows to enter the Assembly treated even the smallest things with care, diligently returning fallen flowerpots to their ledges. A lawmaker’s aide witnessed this stunning act of gentleness amid the chaos.

These stories demand to be told. Without the bravery of ordinary citizens and the restraint of young soldiers, lives would have been lost and Korea might have plunged into unimaginable chaos.

All commanders and high-ranking officers who took part in Yoon’s self-coup have been arrested and now face lengthy trials. Yoon himself is on trial in criminal court. Under Korean law, anyone found guilty of insurrection, such as imposing illegal martial law, can receive only one of two sentences: the death penalty or life imprisonment.

I am profoundly grateful that Korea’s democracy prevailed, thanks to the extraordinary courage of our citizens and the remarkable restraint and wisdom of our young soldiers amid the chaos. And I hold the victims of the 1948 Jeju massacre and the 1980 Gwangju Uprising in my heart. They have indeed rescued us.